Grassington Lead Mines by munki-boy

Grassington Lead Mines

Grassington Lead Mines is in The Yorkshire Dales National Park in England.

Grassington Moor: A Landscape Shaped by Lead Mining

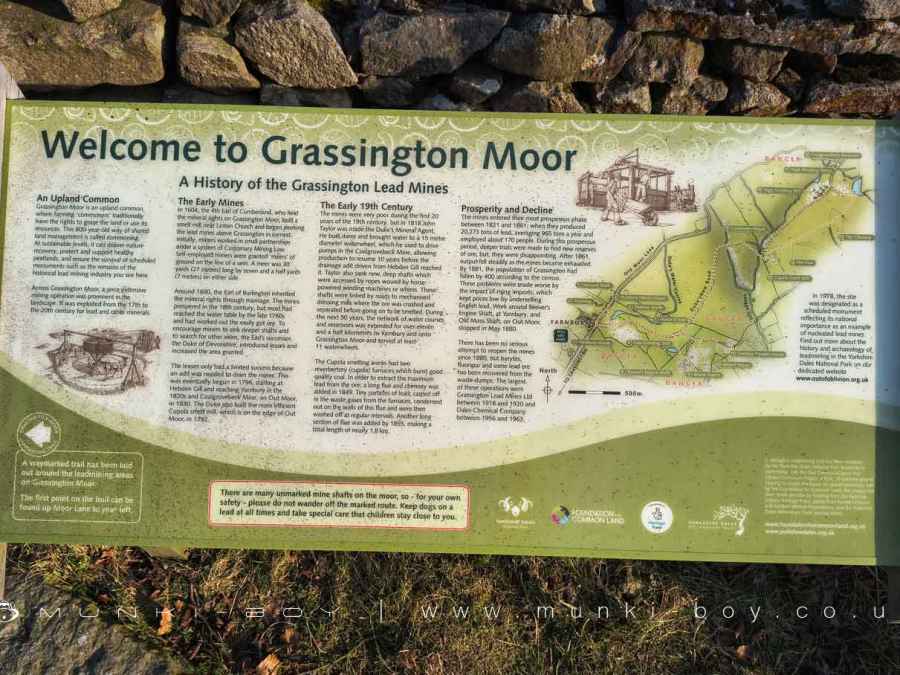

Grassington Moor is a highland common, historically used by local farmers who shared grazing rights and access to its natural resources. This centuries-old practice, known as commoning, has influenced both land management and conservation. Alongside farming, lead mining played a significant role in shaping the moor, with industrial activity spanning from the 1600s to the early 1900s. Today, the remnants of this once-thriving industry remain as visible features in the landscape.

Early Mining and the Rise of the Industry

Lead mining on Grassington Moor dates back to 1604 when the 4th Earl of Cumberland, who controlled the mineral rights, established a smelting mill near Linton Church. Small groups of miners, working under customary laws, were allocated plots of land along lead-bearing veins. These plots, known as ‘meers,’ measured 30 yards in length and extended a short distance on either side of the vein.

By the late 1600s, the Earl of Burlington had inherited control of the mineral rights, and the industry continued to grow. Throughout the 18th century, lead mining flourished, but as operations reached deeper levels, water began flooding the tunnels, making extraction increasingly difficult. In response, the Duke of Devonshire, who later took over the rights, introduced lease agreements and expanded mining areas to encourage further development.

One of the biggest challenges was drainage. Without an effective system to remove water from the mines, deeper excavation was impossible. Work on a drainage tunnel (adit) began in 1796, gradually extending from Hebden Gill to Yarnbury in the 1820s and reaching Coalgrovebeck Mine by 1830. Around the same time, the Duke of Devonshire commissioned a more efficient smelting mill, known as the Cupola Mill, which was completed in 1792.

Innovation and Expansion in the 19th Century

The early 19th century was a difficult time for mining in Grassington, with declining productivity and increasing operational challenges. However, in 1818, John Taylor was appointed as the Duke’s Mineral Agent, and under his leadership, the industry experienced a revival.

Taylor introduced large waterwheels to power pumps, allowing deeper shafts to be drained and bringing previously flooded workings back into operation. He also oversaw the construction of new shafts equipped with horse-powered winding machines, enabling miners to reach greater depths. To process the extracted ore more efficiently, he expanded transport routes and mechanised dressing mills where lead-bearing rock was crushed and separated.

Over the following decades, an extensive network of reservoirs and watercourses was constructed, stretching more than 11 kilometres across the moor. These channels supplied water to at least 85 waterwheels that powered mining and processing equipment.

At the Cupola Smelting Works, reverberatory furnaces were used to extract lead from the ore. As part of improvements made in 1849, a long flue and chimney system was added to capture fine lead particles carried in the furnace smoke. This system was extended further by 1855, reaching nearly 1.8 km in length.

The Peak and Decline of Lead Mining

Between 1821 and 1861, Grassington’s lead mines saw their most productive years, yielding over 20,000 tons of lead—an annual average of 965 tons—and employing around 170 workers. Despite these successes, deeper mining efforts failed to locate new reserves, leading to a steady decline in output after 1861. By 1881, the local population had fallen by 400, reflecting the downturn in the industry.

The situation worsened as imported lead became more widely available, driving prices down and making local operations less viable. By May 1880, mining at Beever’s Engine Shaft in Yarnbury and Old Moss Shaft on Out Moor had ceased, marking the end of large-scale lead extraction in the area.

Although mining never resumed on the same scale, there were later attempts to extract other minerals from the waste heaps. The most significant of these efforts took place between 1916 and 1920, when barytes and fluorspar were recovered, followed by further processing of lead-bearing material by the Dales Chemical Company between 1956 and 1963.

A Preserved Industrial Landscape

Though mining is no longer active, the remains of Grassington Moor’s industrial past are now recognised as an important part of the region’s heritage. Many of the old shafts, dressing floors, reservoirs, and smelting works still stand as evidence of centuries of mining activity. The area’s historical significance has led to its designation as a protected site, ensuring the landscape and its industrial features remain for future generations to explore and learn from.

Caution: Many mine shafts remain unmarked across the moor, making it dangerous to stray from designated paths. Visitors are advised to stay on marked trails, keep dogs on leads, and ensure children remain close at all times.

Created: 9 March 2025 Edited: 2 May 2025

Grassington Lead Mines

Grassington Lead Mines LiDAR Map

please wait...

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

Local History around Grassington Lead Mines

There are some historic monuments around including:

Enclosure S of Bull ScarRed Scar lead mine and ore works, Gate Up Gill, 350m south east of Tag Bale HillHut circle, farm site and enclosures 340yds (310m) NE of Wassa HillYarnbury henge monumentRing cairn 430m south west of Wood EndRing cairn on Kail Hill 380m north east of High Woodhouse.Hydro-electric power house and associated weir 250m north west of Tin BridgeFancarl Top stone circleMedieval farmstead and field system, 530m south east of The GrangeUnenclosed prehistoric hut circle settlement and associated field system and cremation cemetery at Blea GillEnclosures and house sites NE of Hill Castles ScarMulti-period lead mines and processing works and 20th century barytes mill on Grassington MoorRedmayne packhorse bridgeStone circle, Mossy Moor RidgePrehistoric unenclosed hut circle settlement and associated field system at Little WoodTwo settlements in Grass WoodFields and hut circles SE of Scot Gate LaneCairn on Haw HillCairns and settlements on Lea GreenCairn on Old Pasture, 820m south east of Bull ScarSettlement at Chapel House WoodCairn in Brazen Gate Woods 260m NNE of Long AshesGrassington enclosuresLinton churchyard cross and sundialChurchyard cross, BurnsallEnclosures on Old PastureEnclosures 600yds (550m) SE of Wassa HillCairn on Old Pasture 885m NE of Little Lathe.